What is Sub-Saharan Africa

The region of the African continent south of the Sahara Desert is referred to as sub-Saharan Africa. Geographically, the Sahara Desert’s southern boundary serves as the dividing line.

The exceptionally severe environment of the sparsely inhabited Sahara has effectively divided the north and sub-Saharan areas of Africa since the end of the last ice age, producing an effective barrier only broken by the Nile River. Both culturally and geographically, the areas are unique.

The dark-skinned populations south of the Sahara were more isolated from the rest of the world than those in the north, where Arab culture and Islam had a greater effect.

The traditional depiction of the north as above and the south as below is consistent with the current term sub-Saharan.

Equatorial Africa and Tropical Africa are two other names used nowadays to describe the region’s unique environment. But in a strict interpretation, Southern Africa would be excluded because the majority of it is located beyond the Tropics.

Sub-Saharan Africa Geography

With the majority of the continent having remained in its current location for more than 550 million years, Africa is the oldest and most stable landmass on Earth.

Only 10% of its land area is located below a height of 500 feet, making the majority of it a wide plateau.

Humid rainforests may be found close to the equator, but the majority of sub-Saharan Africa is made up of grasslands with sporadic trees to the north and south of that zone.

Along the Atlantic coast in the south is the Kalahari Desert.

Altitude and distance from the equator both have a significant impact on climate. It may be mild in the highlands, even near to the equator.

While there are alternate dry and rainy seasons, precipitation is more reliable in the humid woods.

Also Read: The Benin Empire

Sub-Saharan Africa History

Some geneticists believe that Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly East Africa, is where the human race (the species Homo) first emerged.

The first evidence of stone tools dates to roughly 2.6 million years ago, when H. habilis in Eastern Africa utilized choppers consisting of rounded stones that had been split by straightforward blows.

The Paleolithic, also known as the Old Stone Age, began around this time; its conclusion is thought to have occurred roughly 10,000 years ago, with the end of the last ice age.

Small communities of the continent’s first inhabitants hunted and fished for food. Some humans started living in more stable communities and developed agriculture about 20,000 years ago.

Numerous empires and kingdoms, including the Axum, Wagadu (Ghana), Mali, Nok, Songhai, Kanem-Bornu, Benin, and Great Zimbabwe, have called this region home.

Migration of Peoples

The Bantu migration

The Bantu-speaking peoples are said to have come from West Africa some four thousand years ago.

They migrated and dispersed in many large waves, first moving east (first north of the tropical rainforest to the northern part of East Africa), then south, finally arriving in the third wave to inhabit the central highlands of Africa.

From then, a last southerly migration into the southern parts of Africa took place; this movement may be traced back to roughly two thousand years ago.

The indigenous Khoikoi and Khoisan people were uprooted as a result of the last push towards the southern areas, which led to some language and ethnic mixing.

Compared to the individuals they replaced, they used ironworking techniques that were relatively sophisticated.

Also Read: A Tale of The Bantu People of Africa (Shona, Zulu, Luba, Sukuma, Kikuyu)

A Tale of The Bantu People of Africa (Shona, Zulu, Luba, Sukuma, Kikuyu)

The Zulu expansion

Southern Africa’s slave and ivory trades were growing during the 1700s. King Shaka established the Zulu chiefdom to stave against these pressures.

Conquered tribes then started to migrate north, into modern-day Botswana, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, causing responses there that had long-lasting effects.

For instance, tribes in Botswana started trading ivory and skins for firearms with European traders who had begun to penetrate the interior.

Additionally, missionaries were sent from Europe to the interior, frequently at the invitation of chiefs who desired firearms and were aware that the missionaries’ presence encouraged commerce.

The Ndebele, a branch of the Zulus that had broken away from Shaka and marched north in reaction to the Zulu mfecane, subjugated the Shona in Zimbabwe.

Even now, there are conflicts between the Ndebele and the Shona.

According to estimates from Amnesty International, the Robert Mugabe administration deliberately murdered between 20,000 and 30,000 Ndebele people between 1982 and 1987.

Also Read: Shaka Zulu’ South Africa’s Greatest Army General

Slavery

In Africa, slaves used by African masters were commonly taken captive through raids or as a result of battle, and the captors frequently used the captives for manual labor.

Some slaves were exchanged with other African nations for commodities or services.

One of the earliest slave transactions, coming from East Africa, predates the transatlantic slave trade in Europe by hundreds of years.

While female slaves, especially from Africa, were exported by Arab and Oriental dealers to Middle Eastern nations and kingdoms, some as female maids and others as sexual slaves, male slaves were hired as servants, soldiers, or workers by their masters.

Slaves were captured and transported north across the Sahara Desert and the Indian Ocean region to the Middle East, Persia, and the Indian subcontinent by Arab, African, and Oriental traffickers.

African slaves may have traveled across the Sahara Desert, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean as many times as they did the Atlantic between 650 and 1900 CE, and maybe more. Up until the early 1900s, the Arab slave trade persisted in one way or another.

Trans Atlantic Slave Trade

A lack of labor in South and North America, and subsequently in the United States, led to the beginning of the transatlantic slave trade.

Massive labor was required for both mining at first and the labor-intensive cultivation, harvesting, and semi-processing of cotton, sugar (as well as rum and molasses), and other valuable tropical crops on the estates.

The “slave coast” in Western Africa and subsequently Central Africa served as important supply of new slaves for European traders as a result of this need for labor.

4,000,000 slaves from the Caribbean and 500,000 from Africa were imported by North America. Before the end of the slave trade, South America imported 4.5 million slaves, with Brazil receiving the majority.

The cruel circumstances in which the slaves were carried caused millions more deaths.

Also Read: The Slave Trade in Africa: The Atlantic Slave Trade

The Berlin Conference

It is commonly believed that the Berlin Conference in 1884–1885 formalized the Scramble for Africa by regulating European colonization and commerce in Africa.

The 1880s saw a sharp rise in European interest in Africa. The governing classes in Europe were drawn to Sub-Saharan Africa for racial and economic reasons.

Africa promised Britain, Germany, France, and other nations an open market that would provide a trade surplus at a time when Britain’s trade balance showed a growing deficit, with dwindling and increasingly protectionist European markets as a result of the Depression from 1873 to 1896.

Africa was split among the major European countries at the Berlin Conference. According to one provision of the agreement, a power could only keep colonies if it genuinely had them, that is, if it had signed treaties with the local chiefs, flew its flag there, and established an administration there.

Additionally, the colonial authority had to utilize the colony economically. Another power may occupy the region if the colonial power did not take these actions.

It became critical to establish a strong enough presence to maintain the peace and convince the chiefs to sign a protectorate treaty.

Independence Movements

Following World War II, Africans fought for their governments’ independence, partially in an effort to gain equality of status, modernity, and economic growth that would benefit them.

The majority of sub-Saharan Africa attained independence in the 1960s, with the exception of southern Africa (Angola, Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Namibia, and South Africa).

In a few instances, the military temporarily assumed control of politics, or strongmen in charge of the governments—sometimes on a socialist model—allowed just one political party to exist.

A change to democracy

With its backing for client nations throughout the Cold War, the Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc’s disintegration led to a heightened understanding of the importance of free markets in generating wealth.

The socialist-model-following nations implemented measures to liberalize their economy.

The sub-Saharan governments liberalized their political systems more and more as a result of internal and foreign demand for reform, enabling opposition parties to form and more press freedom.

Politics

Sub-Saharan Africa has made steady progress toward democracy for several years, but recently there have been some setbacks.

Republic of Congo (Brazzaville), Burundi, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Somalia, and South Africa were among the nations that saw reductions, according to Freedom House.

On the plus side, Freedom House stated that the first-ever successful presidential elections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Kinshasa) and advancements in Liberia’s efforts to combat corruption and increase government openness.

Economies

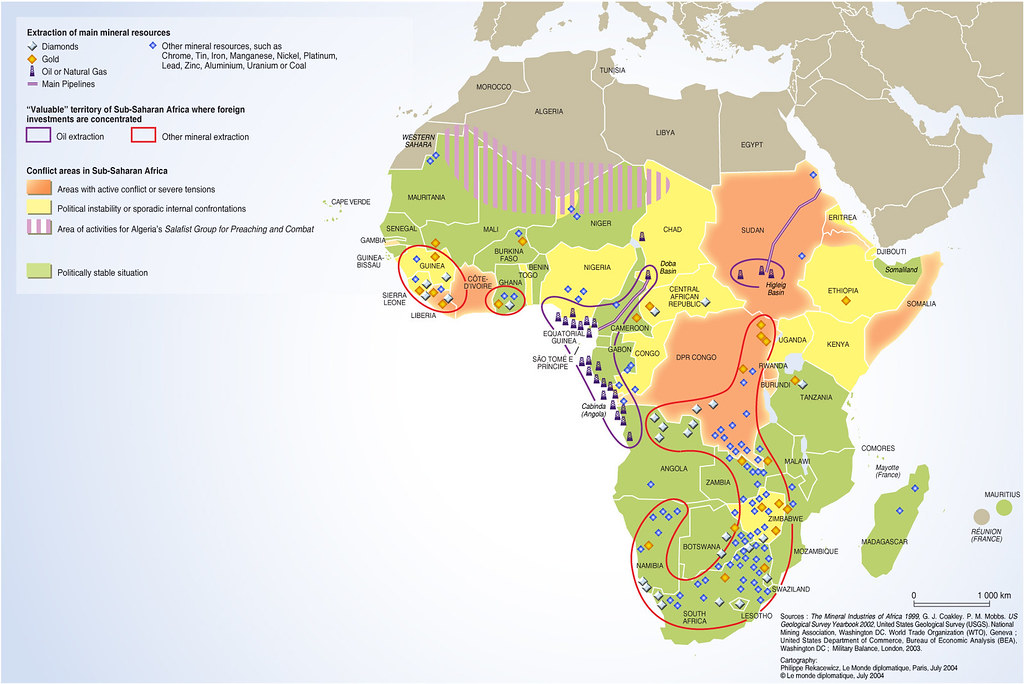

The legacy of colonialism, slavery, local corruption, socialist economic policies, and interethnic warfare still plagues sub-Saharan Africa, making it the poorest continent in the world.

Many of the world’s least developed nations are found in this region.

Many countries struggle to put measures into place that are meant to lessen the impacts of the AIDS pandemic, such the dramatic increase in orphans.

“Sub-Saharan Africa” Racist Undertone

The phrase “sub-Saharan Africa” is frequently used despite making little sense and obviously having racial geopolitical connotations.

A growing number of broadcasters, websites, news organizations, newspapers, magazines, the United Nations and its allied organizations, as well as some governments, authors, and academics, appear to be using the term “sub-Saharan Africa” to refer to all of Africa, with the exception of the five primarily Arab states of north Africa (Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt), and Sudan, a nation in north-central Africa.

Sudan is not included in the “sub-Sahara Africa” label even though the bulk of its land is south of the Sahara Desert because the ruling dictatorship in Khartoum refers to the nation as “Arab” despite the fact that the majority of its citizens are African.

However, the classification “sub-Saharan Africa” is useless, ridiculous, and deceptive. Its use goes against the principles of geography as understood by science and gives racial stereotyping and tired labels precedence.

Classification

On the surface, it is not clear which of the four alternative meanings of the prefix “sub” its users connect to the labeling of “sub-Sahara Africa.” Is it “part of” or “partly” the Sahara Desert, or is it “under” the Sahara Desert?

Or perhaps “partially,” “nearly,” or even the extremely unlikely (hopefully!) application of “in the style of, but inferior to,” the Sahara Desert, especially in light of the fact that there is an Arab ethnic group known as Saharan that is sandwiched between Morocco and Mauritania (northwest Africa)?

Accordingly, “sub-Sahara Africa” is ultimately used by its users to describe an African-led “sovereign” state somewhere in Africa, as opposed to an Arab-led state, rather than some benign construct.

More importantly, “sub-Saharan Africa” is used to create the astonishing illusion of an allegedly diminishing African landmass in the public mind, together with the continent’s allegedly concomitant geostrategic global “irrelevance.”

Unquestionably, the term “Sub-Saharan Africa” serves as a racist geopolitical hallmark whose users continually seek to convey the desolation, aridity, and despair of a desert environment.

This is true despite the fact that the vast majority of Africa’s one billion people do not reside anywhere near the Sahara and that their lives are not significantly impacted by the dogma’s highly charged intended meaning.

Its proponents will eventually succeed in replacing the name of the continent, “Africa,” with “sub-Sahara Africa,” or, worse yet, “sub-Saharans,” in the realm of public memory and reckoning, unless this steadily pervasive use of the term is vigorously challenged by rigorous African-centered scholarship and publicity work.

List of Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa

| Angola Benin Botswana Burkina Faso Burundi Cameroon Cape Verde Central African Republic Chad Comoros Congo (Brazzaville) Congo (Democratic Republic) |

Côte d’Ivoire Djibouti Equatorial Guinea Eritrea Ethiopia Gabon The Gambia Ghana Guinea Guinea-Bissau Kenya Lesotho Liberia |

Madagascar Malawi Mali Mauritania Mauritius Mozambique Namibia Niger Nigeria Réunion Rwanda Sao Tome and Principe Senegal |

Seychelles Sierra Leone Somalia South Africa Sudan Swaziland Tanzania Togo Uganda Western Sahara Zambia Zimbabwe |